In my role as a dean I will have conversations from time to time with alumni or emeritus faculty or philanthropic supporters who have reached an age when they are thinking what they want to make possible beyond their time within our community. Most often donors choose to fund scholarships so that the next generation is supported as they make their own way into the complexities, vexations and joys of humanities study — what could be more laudable? Sometimes a benefactor will endow an annual lecture or event on a topic of deep significance to themselves or their family, such as disability studies or applied ethics. From time to time we receive a bequest that will quietly enable all kinds of future actions through generous, flexible funding — an act of trust in the institution as well as in those who work to ensure that it executes its mission. I love this generosity towards the future, aimed at no one in particular but given in the hope that times to come can be made better for those yet unknown. I oversee a variety of endowments new and venerable that have made all kinds of learning possible here in the humanities at ASU, and I am grateful to those who gave them, sometimes decades ago. These acts have helped me to understand that legacy is what you enable.

But that framing is not universal. Legacy can be for some a trigger to anxiety, even panic or bitterness. Apprehending the universal truth that you will someday be forgotten, that all your great works might not long endure, doesn’t always spur Stoic resignation, let alone a desire to think about how to better a world you no longer inhabit. Having seen some egregious examples, I’ve been reflecting over why some of my fellow academics are needlessly cruel in their evaluations of the work of others, especially of those who are younger but also their peers: as if zingers were points earned redounding to their own reputation, as if anyone cares what they are against (being against things is the easiest exertion in the will; being for things takes work because it obligates you to build). I have seen some scholars — friends, even — who earlier in life railed against the gatekeeping of their elders now attempt to secure those same gates against others, as if the narrowing or “protecting” of their fields were a worthy goal, as if silencing or dismissal were a good look at any career stage … as if fostering and invigorating (both of which involve challenging and are extremely difficult to execute well) were not a better use of their time.

When we in our scholarly or leadership or even philanthropic capacity are granted the opportunity to support others in their intellectual and artistic growth, when we are given the chance to assist in building more strongly towards a future that is uncertain, but instead decide that possibility shall be shut down (sometimes with such vigor that it becomes a perverse point of pride) … well, then we’re just dismantling our disciplines and our refuges from within. I am old enough to have witnessed peers obsess about their legacy, by which they mean that they are anxious that their work will be forgotten, that their books and articles and zingers won’t shimmer with eternal flame. Legacy is not a monument to what you have achieved yourself. If that’s all to which you aspire, I have a reading suggestion. Legacy is what you make possible for those who travel with you, and those who come long after.

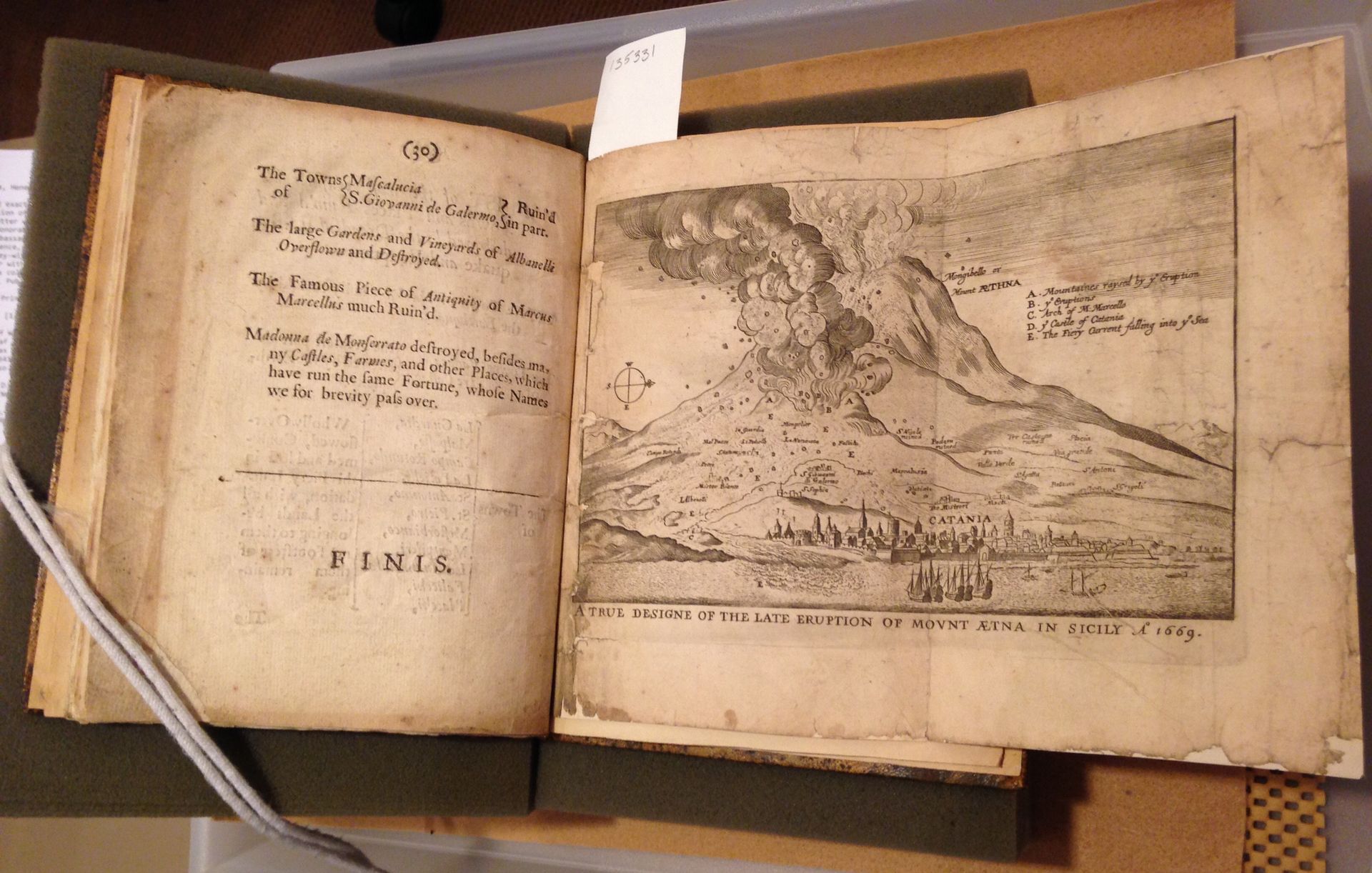

Im once taught a course on disaster and ruin at the Folger Shakespeare Library and would like to think it was a success