[My first published work on monsters, the edited collection Monster Theory: Reading Culture is about to turn thirty years old (and still in print!). Over the next year I hope to use this space to think about monsters studies and the humanities. Today it is sharks, because (1) who doesn’t love sharks? and (2) I have been interviewed a few times recently about sharks as monsters in the wake of the film Jaws now being 50 years old. I speak at the end of the first and the beginning of the second episodes of Radiolab’s Week of Sharks, and have a few things to say about the film’s soundtrack in this ASU News story]

I watched the film Jaws for the first time when I was in sixth grade — the year in which every weekend I would join my oddball group of friends for inexpensive “Polynesian” food and then the short walk to the Waltham Cinema (which only showed movies that were a bit past their prime, but did so at a price a sixth grader could afford). I’d never seen anything like Jaws and was constantly jumping in terror, surprise and laughter (as were my friends: strong emotion is contagious). That night I had an intense dream in which I was being attacked by a shark in my bedroom — a ridiculous dream, objectively speaking, because I was on the top of a bunk bed and Waltham is rather distant from the sea. I remember lying awake with my heart pounding and thinking: how did that movie do that to me? Jaws was in other words a spur to my lifelong study of how monsters work.

Recently I was interviewed by NPR’s Radiolab for their week of sharks. I’ve done quite a few podcast interviews, but this one was hands down the most fun. Late in episode one (Making a Monster) I speak about withholding a total view of a monster as a spur to cognitive uncertainty and sustained suspense, a narrative technique older than Beowulf; early in episode two (The Cage) I list some of my favorite sharksplotation films. I can never not go down a rabbit hole of research though, so below is a quick compendium of thoughts on sharks as monsters. Let me know what you think.

🦈🦈🦈🦈🦈

The shark is an animal that seems to be something more than an animal, a creature that should be easy to classify and contain — and yet one that keeps acting like something more than itself. In honor of the Steven Spielberg film Jaws (1975) turning fifty years old today, I’d like to ask, can a shark be a monster?

On the one hand, a shark is an ordinary oceanic fish familiar to humankind since we started sailing and swimming. These creatures possess a history far more extensive than homo sapiens, having patrolled the depths for at least 200 million years in their modern form. We’ve eaten them and they’ve eaten us for as long as sharks and humans have interacted. This diverse order of fish includes many apex predators and some of the largest non-mammal sea creatures ever to have lived.

Yet shark is a strange word. Perhaps to signify a wolfish nature, these creatures were often called “seadogs” by early modern mariners, giving us terms like dogfish, dog sharks, spiny dogfish and porbeagles. But now English universally designates these long-bodied marine animals with toothy scales and prominent dorsal fins sharks, a noun of uncertain origin that has been in use since at least the mid 15th century and likely derives from a German or Dutch term denoting a malefactor, villain, wrongdoer. As sea-wolves or submarinal villains, sharks swim through the lexicon negatively moralized. And to be honest, when gazing upon a great white shark’s unblinking eyes and row upon row of teeth, allegory easily arrives, propelled by anxieties about engulfment, lethal assimilation, reduction into food.

Despite being fast swimmers some sharks are huge: the largest white shark was 19 feet long and 4400 pounds in weight. Much of the language around sharks is mechanistic, describing them as killing machines or evolution’s perfection of predation. No wonder there is a medical condition known as galeophobia, an exorbitant fear of sharks (from Greek γαλεός, the houndfish, a small shark). Very few sharks are dangerous to humans, but sharks do sometimes attack swimmers and surfers, typically generating outsize media attention. Even though at most four or five people die each year from such encounters, sharks loom large in our imaginations, embodying all the unknown profundities of an ecology that can never be our home.

Yet despite their ability to trigger fear, sharks are in the end just fish, and how can fish be monsters? There are sharks and there are sharks. Most sharks are ordinary creatures of the sea, “a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head … classified within the division Selachii” (Wikipedia). This is the biological shark as affixed by taxonomy to a branch of a diagram in a book, its every secret reduced to epistemic orderliness, domesticated into that which is known. Biological sharks get immobilized on the dissection table or trapped in the aquarium tank. They are in fact fairly harmless, companions rather than malefactors. But there are also sharks that move through the world and through our anxious narratives, no less real than their siblings but freed from the rules that are supposed to govern nature and tame environment into predictability.

Biological sharks are at best monsters in the cryptozoologic sense, real animals that reduce the monstrous to the natural, abating oceanic challenge and containing fear of submergence in and engulfment by the limit after the human. Were biological sharks to go extinct, the world would suffer catastrophic impoverishment, irremediable loss, but humans would endure. The shark on the move though, the creature that brings thalassic engulfment and bodily disintegration crashing upon the human is a true monster in motion. If these sharks did not exist, well then how could we?

🦈🦈🦈🦈🦈

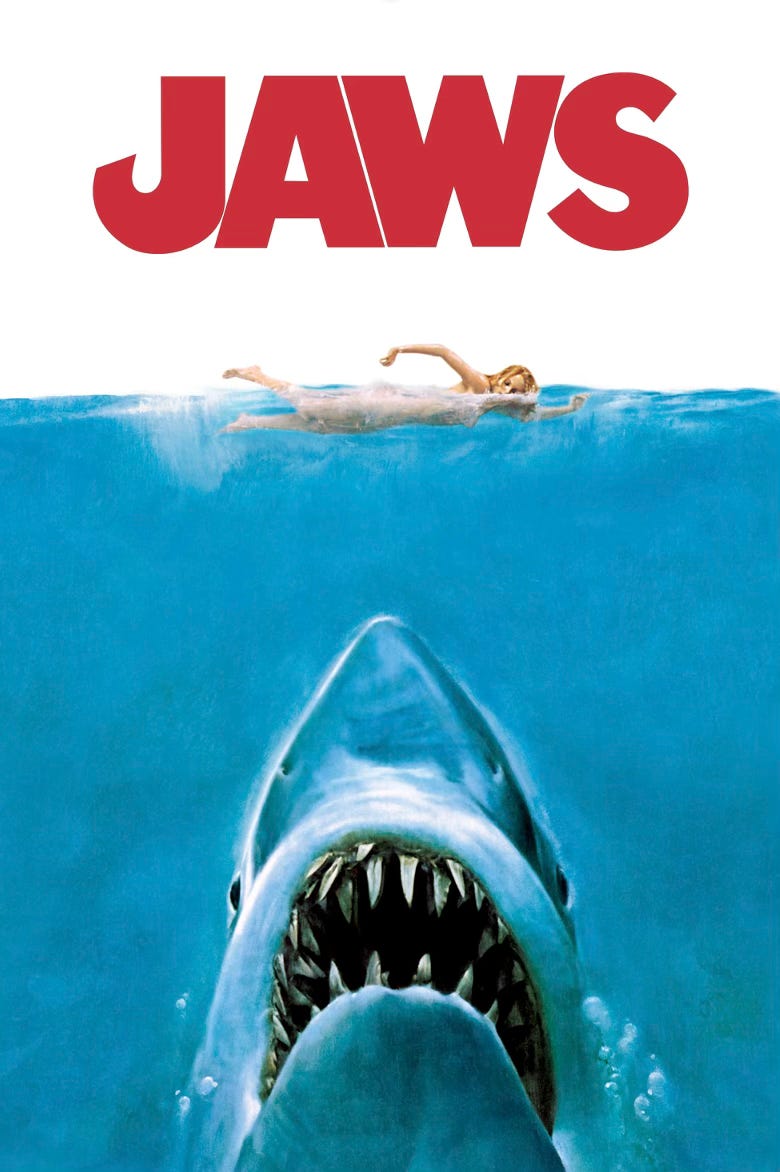

The archetypical shark-as-monster narrative is no doubt Steven Spielberg’s classic film Jaws (1975), based on a novel of the same name by Peter Benchley (who also drafted the screenplay). Now about to celebrate its fiftieth birthday, Jaws was at the time of its release the most lucrative movie ever made, the first real summer blockbuster. The film’s iconic posters depict an enormous shark’s head, open mouth full of teeth, speeding upward to engulf a young woman swimming across deep sea. Not surprisingly then Jaws begins exactly as you would expect for a teen monster thriller. In a beachside town adolescents explore the limits of the permissible through indulgence in sex, alcohol and drugs. Their joy in their bodily freedoms is shattered by a monster who intrudes from their world’s verge to devour them in a way that seems a moral punishment. After a few beers by a fire, a young woman swims naked in the sea, beckoning a young man to join her as prelude to other enjoyments. As he fumbles with his clothing by the shore she is devoured by an unseen creature whose ominous point of view the audience is made to share. A force that engulfs and makes vanish, leaving behind only a bloody trace as warning, this monster endangers relationships, shatters families by ingesting the young. This is the monster that polices the possible, punishing those who break custom and containment. It’s a familiar story effectively depicted through tense underwater and water-level cinematography as well as a famously anxiety inducing soundtrack.

As we move into the second half of the film, however, the young and their fears are left behind. Now the film wonders about the intimacy of monsters and men (in the gendered sense of that word). To avenge the death of her young son, a mother who believes the police have failed to keep the town of Amity safe places a bounty on the shark’s corpse. This incentive to wealth steers a steady food supply into the shark’s jaws as the creature starts feeding on greedy but inept hunters. The film unwinds (as Frederic Jameson made clear) into an allegory of the violence of capitalism, Amity Island as a space engulfed by flows of consumerism and commodity consumption. Chief of police Martin Brody, the hero of the story, finds himself drawn to his own limit by his simultaneous desire to keep the community secure (especially his own boys), to provide for his family by not losing his job (which will happen if he does not obey the mayor and keep the lucrative beach open), and to avoid the open water, an expanse that fills him with phobic dread.

But the film is also more complicated than that. Jaws is a version of Moby-Dick with a shark instead of a whale, and instead of Ahab a veteran named Quint dragged to the ocean floor by the larger than life creature to which he has affixed his obsessions, his fate, and his harpoon. Jaws is as well a human versus marine monster tale that goes back to narratives like Jonah and his swallowing whale, Odysseus against Scylla and Charybdis, or St Brendan on the floating island. Jaws is also a story of man from the “concrete jungle” who fears the sea in the same way that he seems to fear what the man that he is capable of becoming. Manly heroes need their inhuman oceans, stoic embrace of roiled depths.

As the film moves from its focus on teenagers in danger to Chief Brody’s journey to embrace his role as forceful enforcer of order against sharkly predation, we watch him reject the values of the mayor and city council as they seek to maximize summer profits at human expense. In time Brody teams up with marine biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfus, Spielberg’s favorite actor, and often a surrogate for the director himself) to discover how science and the law can unite to forge new roles for Baby Boomer men like them. Brody and Hooper learn, that is, to embrace and transform their inheritance, the heroic masculinity of the Greatest Generation as embodied in sea captain, shark hunter, and WWII veteran Quint.

The captain’s story is anchored in historical fact. Quint states that he is a survivor of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, a ship that while delivering uranium to create the nuclear weapon dropped on Hiroshima was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. Quint narrates a historically accurate tale of loss that includes devastation of the survivors by sharks, who devour the men in the open sea. When Brody and Hooper are left on a sinking ship after Quint has been devoured by the shark, Brody figures out how to relive the sinking of the Indianapolis with a more circumscribed outcome, blowing up the shark rather than detonating an atomic bomb on a city. In doing so he successfully navigates a version of domestic manhood that might work in 1975 (powerful, unafraid, white, patriarchal – there is actually nothing new about it, except that this is a time without the clear human enemies that war provides). The shark teaches Brody how to be the man he needs to become, to leave behind the hesitant version of himself who fears water and self assertion.

Jaws begins as a teen monster movie and ends as a hero’s journey, with all the cliché that genre brings. The film is in some ways far less scary once the clearly mechanical shark head begins to be featured (the film crew dubbed these frequently breaking down machines representing one shark “Bruce”). Yet there is also something about that shark’s relentless mechanicity that works. It’s less a challenge-laden monster and more clearly a brute animal at this point as well, but every time it is underwater and the point of view is shark rather than human ambient anxiety lurks.

🦈🦈🦈🦈🦈

Jaws was so popular that it gave birth to three sequels, culminating in Jaws 3-D, freeing the monster from the screen and bringing it above the heads of moviegoers. More importantly, Jaws introduced the shark as monster in motion trope into the film lexicon. Some of its more worthy descendants include the shark thrillers The Shallows(2016), in which a surfer, grieving the loss of her mother from cancer, battles a white shark off the coast of Mexico (a story as much about being stuck in a world torn apart by grief and loss as it is about inhuman predation); 47 Meters Down (2017), about sisters in a shark cage at the bottom of the ocean in Mexico attempting literal and psychological escapes from entrapment; Open Water (2003), “based on a true story,” featuring a couple trapped in the open sea and trapped in a marriage gone sour, afloat in waters thick with sharks; and The Reef (2010), “based on a true story” in which a group of friends quite literally have their secure life come apart, suffering the wreck of their yacht only to be devoured one by one by a great white shark. Notice that in all of these films the monster-sharks are pedagogical, consuming people to teach survivors some hard truths of the human at its limit.

Yet these sharks are not mere allegories. They are genuinely frightening in that they cannot be reduced to easy, anthropocentric narratives; they pose challenges to facile ideas of human safety in a world that is wider and deeper than it seems. Ron Broglio calls this challenge Animal Revolution.

The shark in Jaws is seldom seen early in the film, its menacing presence artfully suggested by a tense orchestral arrangement by John Williams that has become iconic for its slow build of deep notes and mechanistic forwardness. When the creature does appear, it is machine-like and could almost seem comical; Spielberg is a talented enough director though to disallow that veer. With its relentlessness and refusal to be put into place, the shark operates as a monster in the epistemological sense, consistently challenging the three men on the boat to widen their frame not only for what is possible from the shark but for what is possible from them. The film’s famous line from Chief Brody upon spotting the shark in its immensity for the first time (“we’re going to need a bigger boat”) could also be read as we are going to need a bigger craft, we are going to need a bigger conceptual apparatus to comprehend what this monster in motion enacts.

Jaws stands at the head of an ever proliferating school of shark films. One superfan has created a list of more than 180 movies where the shark is essentially the protagonist. Most of these sharks are exactly what you would expect: hostile dwellers of the ocean depths who intrude into human stories to intensify relations between humans and the world but also humans with each other. But you can find monster sharks almost anywhere. Like zombies, they adapt to most any environment, and can surface their peril where you expect it least. Most of us know about the campy movie Sharknado (2013), which features a swarm of sharks liberated from their oceanic habitat by a cyclone that enables them to dine upon the good people of Los Angles no matter how far they are from the shore. But did you know that it was followed by Sharknado 2: The Second One; Sharknado 3: Oh Hell No!; Sharknado 4: The 4th Awakens; Sharknado 5: Global Swarming; and The Last Sharknado: It’s About Time, which features time travel back to the original Sharknado to either close the loop or open a perpetual temporal spiral, depending on how you look at it.

What is wonderful about these films is that they unleash the shark from its being bound to the sea so that it can prey by air. This franchise is not alone in indulging that fantasy: Sky Sharks (2020) is about Nazi experiments to create flying sharks, unleashed when a secret lab is discovered in Antarctica and the creatures of the Third Reich accidentally unfrozen (there is an allegory here about the survival of white supremacy but it’s a fairly clunky one). The tagline of Jaws was "You'll never go in the water again” – but staying on the beach might not be safer. As you would expect from its title, Sand Sharks (2012) offers a narrative of sharks that swim below sand. Sent by an angry “Native American shaman,” Avalanche Sharks (2014) prey on spring break skiers on the slopes; cf. Ice Sharks (2016), set in the arctic and devoid of teenagers on spring break and shamans but filled with icy sharks all the same. Slightly more reasonably, Shark Night (2011) is about a lake in Louisiana where seven college friends are devoured by a variety of sharks (sharks do not live in fresh water, and yet these sharks live in fresh water). Ozark Sharks (2015) does something similar but in a lake in Alabama, while Swamp Shark (2011) returns us to Louisiana and has the benefit of at least being about animal smuggling rather than vacationers. Bait (2012) places its perilous sharks in a flooded supermarket filled with shoppers. Ghost Shark (2013) demonstrates that you don’t need to wait for a sequel for a shark to come back after you kill it: this shark’s ghost pops right out and continues to kill (and there is of course a sequel, Ghost Shark 2, in which a ghost shark haunts Auckland and an expert ghost shark hunter must be located). Meanwhile The Meg (2018) features a time traveler of sorts, a prehistoric shark. A megalodon somehow survived in the Mariana Trench and reminds moviegoers that to sharks humans are newcomers, albeit delicious ones. Not surprisingly, this film has many progeny that pit the Meg against other primeval survivors, Godzilla-like. Jurassic Shark (2012) is a poor man’s version of the same.

The danger that the shark poses is amplified by monsterizing its body through deformity and addition. Toxic Shark (2017) is about a shark that has evolved to spit acid at its victims from a distance. The film 2-Headed Shark (2012) literally doubles the peril by imagining a shark with two heads terrorizing students enjoying a Semester at Sea. It was followed by 3-Headed Shark Attack (2015), munching upon the passengers of a cruise ship, and the shark-jumping 5 Headed Shark Attack (2017, with the shark endangering a beach resort in Puerto Rico resembling a rather disgusting starfish than anything from Jaws). But of course it does not stop there: 6-Headed Shark (2018) attacks a marriage boot camp. If the allegories were any heavier they would be as lethal as these mutant sharks. These are fun movies, and they love their own intertextuality and unseriousness. When one of the characters in 5 Headed Shark Attack declares "Great whites don't just kill people on boats. What's next, they fly through tornadoes?" he is of course citing Sharknado, a film by the same studio released four years earlier to surprising acclaim.

I have moved here from terror to comedy. My research on giants many decades ago predicted exactly this path for the monster: comedy reduces threat and contains anxiety. It’s hard to tell laughter from fear, and fear from desire. The power of the monster resides in the strong feeling it elicits, and that strong feeling is the sense of the limit of the human being breached. The monster stands at the limit of the possible. I learned that long ago.